DQ Blog

Recent Musings…

SLOW-RIPENING FRUIT

May 12, 2023. Bozeman. The long winter is finally over, the dropped Halloween candy and lost newspapers have melted out of the snowbanks, the tulips and daffodils are up, the geese are sternly defending their nests, and the click of golf clubs against Titleist 4s...

Zoom

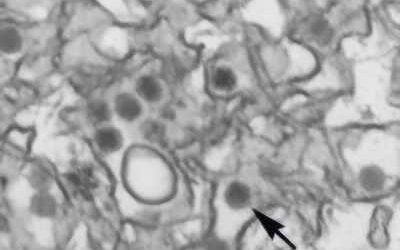

Whew. It's been a busy three years for me, mostly spent researching and writing about the pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, and its fierce journey through the human population. (See the article on Breathless, just to the left.) For most of that time, I stayed home in my...

Little Things

Here's an interesting fact that you might want to swirl around in your head, along with a sip of the morning coffee: Scientists have now assembled and archived more than 12 million genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Each of those...

Springtime in the Rockies

Douglas, Wyoming April 23, 2022 It seemed like a good idea at the time: I would drive to Cincinnati, for an unmissable event at my old high school, making it a leisurely road trip, taking along a bag of golf clubs, stopping to golf with my friend Whisperin' Jack (the...

Up For Air

January 2, 2022 WHOOSH: And so a year has passed since I last updated this blog. I have an excuse for the neglect: book deadline. The pandemic began, I set aside one book in progress, and in March 2020 committed to Simon &...

Enduring and Remembering

JANUARY 16, 2021 Did I say holy goodness? Holy crap. What a year. I've got scant appetite for describing what it's been like for me, because chances are it was worse for you, and I honor that. Difficult for everybody, but my family and most of my friends have...